Non-Invasive Mechanical Ventilation (NIV) and SCI

NIV provides respiratory support without the need for intubation and bypassing the upper airway. In comparison to invasive mechanical ventilation, it is associated with fewer complications, preserves the upper airway defense mechanism, permits speech and is used with greater comfort.

NIV often has a key role in providing respiratory support for a person with a SCI to maximise respiratory function but also prevent respiratory complications. The main challenge is developing user tolerance and compliance with the optimal interface.

Clinical indicators for benefitting from NIV support:

- acute, high-level and/or multi-trauma SCI to:

- improve minute by improving tidal volume

- improve alveolar ventilation by increasing functional residual capacity

- correct nocturnal ventilation to enhance daytime ventilation

- reduce the work of breathing and manage respiratory fatigue over a long period eg. 24hrs+

- manage the multifactorial risk of acute respiratory failure

- avoid complications related to invasive ventilation and tracheostomy

- preserve glottal function including swallow and voice

- post-acute high-level SCI with ongoing ventilation support needs but assessed capacity to trial and manage with NIV

- chronic management of a person with SCI for the treatment of sleep disordered breathing eg. sleep apnoea.

NOTE:

- NIV is

- prescribed by a medical physician, preferably a respiratory specialist if needed long-term

- requires careful monitoring and titration, especially with supplemental oxygen therapy to ensure its success and avoid complications eg. gastric distension and aspiration, respiratory alkalosis

- NIV can be

- delivered via nasal and nostril pillow, mouthpiece and face mask +/- humidification

- more portable in a travel bag than some ventilators

- Contraindications and precautions for use of NIV include but are not limited to:

- severe facial injuries

- undrained pneumothoraces and tracheoesophageal fistula

- poorly controlled intracranial pressures

- swallowing disorders

- inability to maintain effective coughing over a prolonged period

- poor comprehension and cooperation

- poor ventilatory status

- NIV daytime use should be weaned before NIV night-time use: consider sleep disordered breathing and impact on daytime ventilation

- NIV tolerance and compliance needs to be built and will likely require personalised trials of various interfaces

While developing a ventilation management plan is crucial, it is important to first:

- complete a comprehensive respiratory function assessment

- consider integration with a lung volume inflation/recruitment and secretion management plan

- have a multidisciplinary approach to management and intervention

Types of NIV

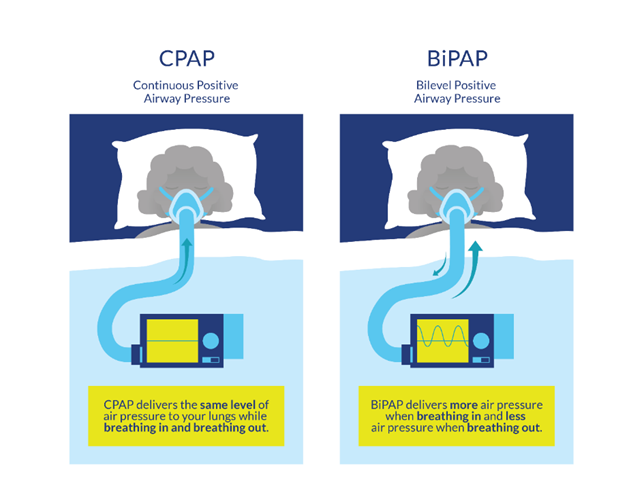

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP)

- allows unrestricted spontaneous breathing

- provides a constant positive pressure during inspiration and expiration (between 5-10cmH2O)

- uses low level positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) to assist splinting of the airway during quiet expiration:

- preventing airway collapsefacilitating collateral ventilation to improve arterial O2 levels

- increasing functional residual volume and gas pressure behind secretions

Bi-level Positive Airway Pressure Ventilation (BiPAP)

- allows unrestricted spontaneous breathing

- splints the upper airway and manage obstructive sleep apnoea due to malposition of the tongue during REM sleep

- utilises a positive pressure cycling mode during which varies between inspiration to expiration

- establishes a pressure gradient difference between inspiration and expiration:

- increasing tidal volumes while delivering pressure support to the lungsimproving arterial CO2 levels

- reducing the work of breathing

CPAP and BiLevel PAP Ventilation Source: https://community.scireproject.com/topic/sleep-disordered-breathing/#treatment-available-for-sleep-disordered-breathing

Daytime + Nighttime NIV

A C3 level SCI, or C4-5 level SCI with significant hemi-diaphragm dysfunction, may also require lifetime full or part time ventilator dependency due to significant diaphragm weakness; some will be able to transition to non-invasive ventilation management (NIV):

- daytime mouthpiece/sip and puff NIV

- nighttime nasal/nostril pillow NIV

Weaning to NIV and Extubation/Decannulation

General clinical considerations include:

- functional vital capacity >1500ml

- peak cough flow rate > 160-270L/min

- clear lungs and a normal chest x-ray

- stable blood gases, heart rate and respiratory rate

- afebrile

- stable secretion levels

- positioning ie. consider the work of breathing, use of abdominal binder

- timing ie. not at the end of the day, not at the start of a weekend

- when fatigued

- when MDT staffing supports and services are reduced

Staged clinical processes to introduce include:

- increased tidal volumes, for improving lung and chest wall compliance

- intermittent positive pressure breathing (IPPB) strategies, including breath stacking and non-invasive secretion management strategies for development of adequate peak cough flow

- inspiratory muscle training (IMT) including activation of accessory muscles

- trials to determine best NIV interface for optimal tolerance and compliance

- weaning to NIV support ventilation starting with the day+/- periods of ventilator free breathing, the introduce overnight NIV

- starting with cuff deflation then progressing to cuffless insert

- weaning first and only progressing to extubation/decannulation if successful

Discharge planning and community considerations:

A person with SCI who requires mechanical ventilation on discharge, including non-invasive ventilation eg. sleep disordered breathing, should have a respiratory health plan and respiratory care plan developed by the treating multidisciplinary team.

This is essential for NDIS participants to establish disability health-related needs to secure funding for care planning, capacity building supports and assistive technology needs.

Refer to Community Respiratory Care and Health Plans

Resources

Sheel AW, Welch JF, Townson AF (2018). Respiratory Management Following Spinal Cord Injury. In: Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, Connolly SJ, Noonan VK, Loh E, Sproule S, McIntyre A, Querée M, editors. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence. Version 6.0. Vancouver: p. 1-72 https://scireproject.com/evidence/respiratory-management-rehab-phase/sleep-disordered-breathing-in-sci/

Popowicz P, Leonard K. (2022) Noninvasive Ventilation and Oxygenation Strategies. Surg Clin North Am. Feb;102(1):149-157 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8598279/

Harvey, L. (2008) Management of spinal cord injury: A guide for physiotherapists Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone. https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780443068584/management-of-spinal-cord-injuries

Spinal Cord Injury Guidelines (2021) Department of physical medicine and rehabilitation/trauma rehabilitation resource program. Lim, A., Pristas, N,. in collaboration with the TRIUMPH Team led by Medical Directors Thomas S. Kiser, M.D. and Rani Haley Lindberg, M.D. Updated by Thomas S. Kiser M.D. on 1/17/2021 https://medicine.uams.edu/pmr/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2021/02/Guidelines-SCI-Respiratory-2021.pdf